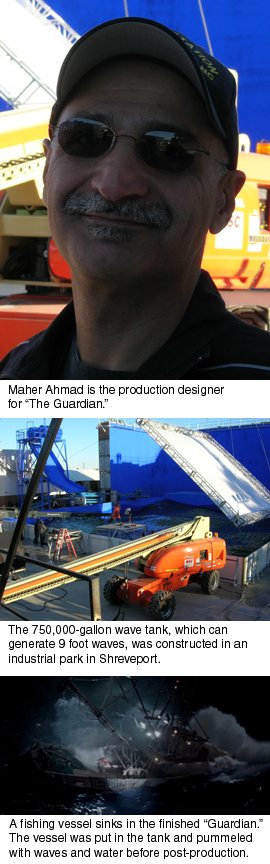

Many of the waves in "The Guardian" were created within a 750,000-gallon wave tank in Shreveport. Maher Ahmad, the movie's production designer, played a big role in creating them.

He designed the tank, which measured 80 feet wide, 100 feet long and eight feet deep.

Surrounding half of it was a five-story cyclorama that was painted bright blue. It served as a giant blue screen.

The other half was surrounded by splash guards. They could be removed to get cranes, cameras, crew and actors in and out of the tank.

Dump tanks, or 4000-gallon drums, released water down chutes and onto the actors and vessels.

Three 150-horsepower fans and eight hidden chambers were used to generate waves that measured nine feet or more from the top to the bottom of their swells.

In other words, there was some serious wave-making going on. I sent seven questions to Mr. Ahmad. Below are his answers.

Alexandyr Kent: The Bering Sea is as much a character in the movie as Costner’s Ben Randall and Kutcher’s Jake Fischer, and a huge part of those rescue scenes were filmed in a 750,000-gallon wave tank in Shreveport. How challenging was it to create this “monster of nature,” as director Andrew Davis termed it, within a land-bound industrial park?

Maher Ahmad: The fact that we were using a basically untested approach to the making of waves, and the additional pressures of time and budget, and the fact that we had already started building the tank once in New Orleans and had to start all over again in Shreveport made it very difficult job indeed. It took the coordination of not only my efforts coupled with the our construction coordinator and his crew; the paint dept and its crew; the special effects and stunt departments and their crew; but also the outside work of a variety of engineers (including structural, environmental, soil, mechanical, and electrical engineers). And on top of that, we had to deal with a scarcity of labor, materials, equipment, and supplies that was due to reconstruction efforts going on in New Orleans.

AK: As the production designer for “The Guardian,” how did you balance the audience's desire for thrills with the story's demand for drama? Was there ever a point at which you feared the sea would overpower the storyline?

MA: Those kinds of decisions are really more the province of the writing, directing, and editing than any decisions that I make. I gave them the sets and the environment; the director and writers decide what to shoot and with the director the editor decides what specifically the audience sees.

AK: Technically, what was this wave tank capable of creating? How big were those waves during the rescue sequences? When we watch the film with rolling water and the blowing wind, it looks like the actors are in trouble.

MA: Because the tank was pneumatic rather than mechanical, we had great control over the kinds and the power of the waves we could make. We actually never had the power up full during any of the scenes. We got six-foot swells and troughs but we probably were capable of making them much, much bigger.

AK: What effect in the film is your favorite, and how did it add to the tension of the scene?

MA: For me, my attitude to the work I do on my films is that of a good parent: I love them all, although some my be different than others, some may be more successful or attract more attention than others, they are all pretty wonderful, and I love them equally.

AK: Tell me a bit about the scene when the rescue swimmers (Kutcher and Costner) save the kayakers in the cave. You installed a cave in the wave tank. How big was it? What did you do to make the environment and the water inside the cave look so authentic and threatening?

MA: The cave was a 150,000-pound set that was built from steel, rebar, foam, and plastic next to the set and then moved by two 150 ton cranes and dropped into the tank. It had to withstand a terrible beating form the force of the waves. It was about 40 feet high, and 80 feet wide and about 60 feet long. It was open three feet at the bottom which caused the waves to bash against it in a realistic manner.

AK: You have rolled a passenger jet over for “U.S. Marshals” and sunk a pirate ship for “Miss Congeniality 2.” Was creating the effects for “The Guardian” just another day at the office, or was the challenge especially demanding?

MA: Every aspect of every film has its own particular demands and problems. "The Guardian" was by far the biggest water picture effort that I have done and the previous films that I did that had water work were a good preparation for what we all managed to pull off in Shreveport.

AK: Lastly, was there ever a point when Costner, Kutcher, the actors and the stunt doubles said, “Maher, enough with the crashing waves already. I can’t take it anymore!” Did you really beat them up as much as it appears in “The Guardian?”

MA: Again, I was not directly responsible for how long the actors spent in the water, or what they were required to do while in it. It is the director and the stunt coordinator that subject them minute by minute to the rigors of the tank. However, it is indeed the fact that the actors were heroic in how hard they worked, and how little complaint they made, under extremely difficult circumstances.

____

The wave tank is now owned by Ken Atchity and a group of investors. The facility is now called the Louisiana Wave Studio. I'll talk with Mr. Atchity about the future of the facility soon.

No comments:

Post a Comment